Transformation Through Forgiveness Monument

Monument to Foregiveness Returns to Northeastern State University

by Nancy M. Garber

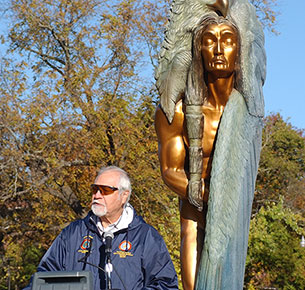

On June 20, 2016, a traveling bronze monument that has completed its sojourn across America will be formally unveiled and re-dedicated at the Tahlequah, Oklahoma campus of Northeastern State University.

The Monument to Forgiveness, created by Dutch-born sculptor Francis Jansen, resided south of historic Seminary Hall from August 2001 until November 2002, before continuing its journey. Last year, the artist donated the 15-foot tall bronze replica of her original marble statue to the university. Eagle Man, standing atop a turtle base near the end of the historic Trail of Tears, will serve as a perpetual reminder that the power of forgiveness dwells in all of us.

Unveiling - August 2001

Long before Oklahoma statehood in 1907, the springs that feed Town Branch Creek as it flows through Tahlequah became a traditional gathering spot for settlers. Rural folks drove their horses and buggies to town and parked them beside the cool, clear water while they conducted business and exchanged news of the day. Students of the Cherokee National Female Seminary gathered there for events and ceremonies, as would their counterparts into the 21st century. History was often made there: in 1887, the murder of a U.S. marshal sparked one of the most famous manhunts in Indian Territory lore.

Flash forward to the 1990s. Several Northeastern State University educators began drawing up plans to erect a monument that would mark the terminus of the Trail of Tears on Beta Field, adjacent to Town Branch Creek. Students, local citizens, and visitors to the area would be reminded of the suffering endured by thousands during the tragic removal of Cherokees in the 1830s from the mountains of North Carolina. Upon their arrival in Tahlequah, the new capital of the Cherokee Nation, survivors would settle and begin to rebuild their lives.

For lack of funds, plans were shelved but not forgotten. Meanwhile, no one could have predicted that a California sculptor had recently completed a monument destined to honor the Cherokees and other indigenous peoples across the globe.

In August 2001, the traveling Monument to Forgiveness was unveiled at Beta Field, near the banks of Town Branch Creek. Standing watch day and night over historic downtown Tahlequah, the statue fulfilled, and even surpassed, what earlier planners had in mind. It also acknowledged the transgressions of the past and inspired reconciliation through forgiveness.

The timing was serendipitous. Within days, the nation would experience the first horrific attack on home soil since the U.S. Civil War. For the next 15 months, visitors and passersby would draw comfort from the monument's steady reminder that the need for reconciliation never really ends.

I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free. Michelangelo

The work of Francis Jansen, born in 1946 in a fishing village in the north of The Netherlands, has been likened to that of the classic sculptor, Michelangelo. She began life in the aftermath of World War II. Her father had been part of the Resistance Movement in war-torn Europe and her parents were forced into hiding for two years toward the end of the war. The family immigrated to Australia when Jansen was six years old and after completing her secondary education, she returned to Europe with her family in 1964, at the age of 18.

As a young adult she received training and worked in a variety of jobs, from hair stylist to laboratory technician and doctor's assistant. In 1967, Jansen wed a United Nations diplomat and lived the next six years in Thailand during the Vietnam War. She had the opportunity to travel extensively throughout war-torn Asia, and was exposed to various cultures and value systems. Then in 1977, while in the process of divorce, Jansen and her four-year-old son immigrated to the United States. There she began a new life, first as owner and operator of a large natural foods restaurant, until the strenuous demands of entrepreneurship eventually compromised her health and well-being. This turning point led her to an in-depth exploration of the holistic healing arts, and Jansen began to experience firsthand the powerful role that emotional, mental, and spiritual health has on the physical body.

With new understanding and direction, Jansen embarked on backpacking ventures in the mountains of Southern California, where she learned to communicate with the elements, plants, and animals. Her experiences in nature led her to become an advocate and protector of the land. And she began to feel a particular kinship with the stone people, known in some Native American cultures as the ancient ones who hold the knowledge of the world.

The question that has inspired all of my work has always been, how can I assist the expression of the sacred here on earth? My sculptures are reminders for all of us of the sentience of all living things with which we are blessed to share this beautiful planet, Jansen said.

In 1988, with no previous art training, Jansen began to sculpt in stone. She had the gift of sensing and envisioning beings in the stone, and so she set about the daunting task of learning how to carve and set them free.

A year later, Jansen traveled to Carrara, Italy. There she explored the exquisite marble quarries that have yielded white and blue-gray marble since the time of ancient Rome, used to create world famous sculptures and building's cor, including Michelangelo's David. The artist was drawn to a large, elongated block of marble, thirteen feet long and weighing eight tons. Within the stone, she saw a vision. It became her destiny to release it, to set it free.

I had a real heart-opening, a feeling of wow, this is beautiful, and right at that moment, I had the vision of a Native American man lying with his face on the ground, and felt compelled to bring the immense block of marble back to the United States, Jansen said in an interview with Cable News Network.

In the year 1991, from January through September, she spent her days in her outdoor studio, on scaffolding, mindfully and lovingly sculpting with hammer and chisel. Each chink of the marble confirmed a growing awareness that she would reveal a being of special significance.

During what the artist described as an arduous and euphoric birthing process, her vision began to manifest itself into Eagle Man: a seven-ton, 12-foot tall marble monument.

I literally fell in love with the being that dwelled within [the stone], she remembered. I knew this being was part of myself. He brought me to my knees to face my own un-forgiveness -- not just what I had been holding against others, but what had I been holding toward myself.

Jansen, who is also a holistic therapist, recognized the life-changing message revealed through her art. If every day we took responsibility for our own suffering and asked, what hatred, what anguish, what pain am I still holding onto? we wouldn't need to project it onto the world to reflect our suffering back to us.

Overwhelmed with a sense of gratitude for what she'd been able to achieve and inspired by its potential to change the world, she created a non-profit foundation called Transformation Through Forgiveness. Jansen foresaw the monument that began as a block of marble in an Italian quarry as the anchor for a global movement of forgiveness and reconciliation.

Her original marble sculpture, unveiled in 1993, stood across the street from the Santa Barbara Mission on ancestral land of the Chumash, a Native American tribe that has inhabited the coast of California for the past 13,000 years. The Chumash population was devastated by the clash of cultures that occurred when Spain began settling the west coast of North America.

At the Santa Barbara Mission, Eagle Man became a symbol of reconciliation to atone the transgressions of early settlers. Afterward, Jansen was told by many in the community that the energy within the vicinity of the statue had shifted. The site became a popular local attraction where people deposited flowers, eagle feathers, forgiveness letters, fruit, and other gratitude objects and mementoes around the base of the statue. Couples were married there and drum and prayer circles gathered, along with other ceremonies and events.

These are the kinds of things we as humans can do to reconcile and pull energy together, in search of forgiveness for our ancestors, Jansen said. She realized that it would take more than herself alone to petition forgiveness for their transgressions, and just at that time Francis got an unexpected phone call from a man in The Netherlands who offered a generous donation to support this endeavor.

With the donor's help, an exact, full-size bronze replica of Eagle Man was created to journey across the United States, as a symbol and gesture of forgiveness. Eagle Man takes the form of a half man, the sides of his body connected by an eagle draped across his head, mounted on a large turtle base. The first unveiling took place in 1998 on the Nez Perce Indian hunting grounds at Wallowa Lake in Joseph, Oregon. From there, the bronze monument embarked on a ceremonial pilgrimage to encourage reflection, inspire compassion, create tolerance, and evoke humility, according to Jansen. The next stop was Southern Oregon University in Ashland. From there, the monument would find its way to Tahlequah.

I wasn't voted to do this by the people of The Netherlands. This is my soul's calling, a covenant with my spirit self. It's my own way of making a gesture toward righting the wrongs of the past, and for my ancestors. Francis Jansen

When I first came to this country and was hiking around, it felt like there was a heaviness to the earth the blood stains on the ground that were calling out to be reconciled. I was inspired to help lift that heaviness through a gesture of reconciliation for man's inhumanity to man, Jansen recalled.

I really felt like this monument was from my ancestors to the native peoples, to encourage reconnecting in a way that doesn't change or disregard the past, but is a bridge to healing for all of us. Forgiveness is that bridge.

The California-based artist first became aware that NSU was willing to host the Monument to Forgiveness through correspondence with Kathryn Robinson, whom she had met at SOU. When Robinson was named dean of the NSU College of Arts and Letters, she approached university administrators, who quickly connected the dots between Jansen's theme of reconciliation and Tahlequah's historic significance as the terminus of the Trail of Tears.

On the morning of Friday, August 31, 2001, under a cloudless blue sky, members of the NSU Native American Students Association led a processional of flags representing Oklahoma's tribal nations to the entrance of campus, accompanied by student members of the HOPE Club from Sequoyah High School. With an introduction by Robinson, NSU President Larry Williams welcomed the assemblage, and introduced guest speakers from the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and the United Keetoowah Band. As the statue was unveiled, the artist recalled seeing eagles flying overhead.

Kathryn did a beautiful job with the unveiling, Jansen said. It was a stunning experience, one that felt deeply connected to the earth and the ancestors.

Crosslin Smith, a well-known traditional Cherokee medicine man, blessed the monument. Pow-wow dancer Clayton Daylight performed The Eagle Man, and Larry Daylight, a professor at Bacone College, spoke about the significance of the eagle in Native American culture. Tonya Still, the reigning Miss Indian Oklahoma, offered a traditional flute solo. Their tributes segued into Jansen's presentation about the meaning behind her impressive sculpture and how it came to be.

Delores Sumner, now retired as NSU Special Collections librarian and of Comanche heritage, was among those in the audience that day. She appreciated the use of the eagle as a symbol of forgiveness.

The eagle means strength and power, and this statue tells us that to forgive is not an act of weakness, but of strength, Sumner said, following the ceremony.

Jansen later told NSU's student newspaper, The Northeastern, We need a lot of healing in America, especially where there has been intense discrimination and injustices. It is through the willingness to forgive that there is the possibility that we can heal emotionally.

Forgiveness Put To the Test

Forgiveness, as represented by the eagle whose wings swept and dominated the monument standing watch over the historic capital of the Cherokee Nation, faced an unprecedented challenge just twelve days after the unveiling. On September 11, terrorist attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C., and in a field in rural Pennsylvania, shook the nation to its core. Fear and uncertainty about the future permeated life at all levels. Eagle Man became Tahlequah's unofficial symbol of hope.

Jerry Cook, who was mayor of Tahlequah in 2001 and now serves as NSU's director of community and government relations, recalled students and local citizens gathering at the base of the statue for a special ceremony to honor victims of the attacks.

Students placed small American flags into the ground near the statue and across Beta Field. People came together and shared their grief. It was prophetic that the Monument to Forgiveness was left on our campus just days before the 911 attacks.

In a letter to Jansen, Robinson described the monument's significance to the community as a rallying point of grief as Americans coped with understanding violence against civilians.

Sitting at the entryway to campus, the Eagle Man welcomed the questions of a shaken people, giving comfort if not answers, she noted. People from all walks of life, at any time of day or night, were offered guidance to look inward for the voice of forgiveness.

During its time in Tahlequah, the monument came to the attention of Mary Jane Letts, an NSU graduate living in Cherokee, North Carolina. She was so impressed by its significance to all Cherokee people that she asked Jansen to consider the beginning point of the Trail of Tears as the statue's next destination.

In November 2002 a farewell ceremony was held in Tahlequah. Cherokee tribal leader John Ketcher addressed the crowd, along with President Williams and university students. With a traditional Cherokee blessing to send the statue on its journey and parting words from Jansen, the Monument to Forgiveness traveled to the capital of the Eastern Band of the Cherokees, where it would remain for the next 13 years.

Shortly after the monument's departure, Williams suggested in a letter to Jansen that NSU might one day be considered as its permanent home. In 2015, Jansen contacted university officials with an offer to donate the bronze replica of her original marble monument, which stands 15 feet tall, weighs 3,000 pounds, and has a certified appraised replacement value of $250,000.

By placing the monument at NSU, Jansen hopes to foster reconciliation in perpetuity for the suffering endured by Native Americans along the Trail of Tears.

Last August, following the formal transfer of ownership to the university, Cook and his wife, Barbra, brought the statue home from North Carolina. Cook was among the speakers during a farewell ceremony that included civic and tribal leaders. Once the bronze monument was securely strapped into a harness and laid horizontally on a 20-foot trailer, Eagle Man began his 900-mile return trip to Tahlequah, eyes skyward. Motorists and other travelers at rest stops along Interstate 40 were intrigued by the Cooks unusual cargo.

Folks would surround the trailer when we pulled into a station for gasoline and want to know what we were carrying and where it was going, Cook noted. They wanted to know the story behind the statue. A lot of people were photographed with Eagle Man, and we saw several taking pictures through their car windows as we drove past.

Last September, Jansen traveled to Tahlequah and helped select the exact spot on Beta Field where the monument will be permanently mounted. She marked the location by implanting a white crystal into the ground, upon which a concrete base, 10 feet in diameter, has since been centered. The statue will stand along a path where students from the Cherokee National Female Seminary once walked to town, not far from where it was in 2001. The exact alignment of Eagle Man's face was determined with the help of the artist and the shaman who accompanied her. Lighting around the base of the statue will illuminate five plaques that tell the story of Jansen and her journey to create the Monument to Forgiveness.

The whole area around Beta Field has a complex history and disrupted energy to it, Jansen said. When the monument is unveiled, the collective prayers and intentions of our ceremony will be directed toward the healing and transformation of this history and these energies. In this way, the ground becomes hallowed ground. It becomes sacred.

Visitors to the site will get to know the artist and understand her inspiration to create through Jansen's own words, inscribed in perpetuity at the base of the monument: Forgiveness begins in the heart of each one of us forgiveness of the Other being intimately entwined with forgiveness of Self.

For more information about the Monument to Forgiveness and Francis Jansen visit https://www.tahlequahdailypress.com/news/artist-donates-transformation-statue-to-nsu/article_bf4a80e8-531b-11e5-907a-fbbdf7b1140b.html and GraceInStone.com.